A Milano la Galleria Raffaella Cortese presenta la seconda mostra personale dell’artista Alejandro Cesarco dal titolo The Measures of Memory. Una indagine sul tema della memoria, intesa come oggetto e al tempo stesso strumento dei nostri desideri, attuata mettendo in relazione diverse metodologie di documentazione, descrizione e misurazione del passaggio del tempo, e le forme utilizzate per rievocarlo. La mostra è caratterizzata da un tono romantico e a tratti malinconico, tipico di tutta la produzione dell’autore, che favorisce l’esplorazione di categorie quali narrazione personale, stile, invecchiamento, influenza ed eredità.

Francesca Interlenghi: Alejandro, si parla spesso di te come di un artista che riprende la tradizione e continua la narrazione dell’arte concettuale degli anni Sessanta e Settanta. Ti confesso che non sono molto amante delle definizioni, ma in questa ti ci ritrovi?

Alejandro Cesarco: Capisco perché venga utilizzata. Si tratta di una formula abbreviata che riassume molte cose, ma non sono certo che abbia davvero senso. Non so bene che cosa si intenda o quali siano i requisiti che un’opera deve possedere per essere annoverata tra quelle della tradizione perché, in una certa misura, tutta l’arte è concettuale.

F: Sul fatto che in qualche modo tutta l’arte sia concettuale concordo perfettamente.

A: Credo che la definizione necessiti di ulteriori precisazioni. D’altro canto, è vero che subisco la fascinazione del concettualismo inteso come “ismo”, come movimento, perciò molti degli aspetti formali del mio lavoro fanno riferimento a opere degli anni Sessanta e Settanta.

F: Studiando il tuo lavoro direi che spesso vi ho visto una intersezione di razionalismo e poesia, un dialogo vicendevole direi. Nello spazio tra la tua visione razionale e la tua percezione emotiva si dipana tutta la tua produzione artistica. Mi puoi spiegare come nasce il processo artistico? Voglio dire: sono molto interessata a capire come trovi un bilanciamento, un punto di contatto, tra visione razionale e percezione emotiva in maniera così irrinunciabile.

A: Credo che molta della mia produzione riguardi questa tensione che tu hai espresso, nel senso che si tratta quasi di mantenere l’intimità a distanza, misurando da quale luogo risulti più confortevole parlarne. Ma si tratta anche di infondere in questi contenitori apparentemente freddi di cui stiamo discutendo, in queste forme concettuali, quello che sembra essere un contenuto intimo. Di conseguenza anche il tema dell’intimità viene indagato perché sembra che qualcosa di molto intimo sia proposto senza che alcun aneddoto venga veramente svelato. Quindi significa davvero parlare di affetto e, in certa misura, di come venga percepito il suo significato. Ma ancora una volta, proprio come per la parola concettuale, ci può essere razionalità senza emozione? L’una non esclude l’altra, nel senso che inevitabilmente coesistono.

F: Credo che tutto ciò che abbia a che fare con l’essere umano sia per certi versi romantico o sentimentale, emozionale sarebbe più appropriato dire. E’ molto interessante notare quanto il linguaggio permei la tua pratica artistica e capire dove venga meno la distinzione tra l’atto del leggere e quello del guardare. Mi riferisco per esempio al tuo video “The Inner Shadow” un’opera davvero bella e toccante. (N.d.r. The Inner Shadow, 2016, pellicola 8mm a colori trasferita su digitale, suono, 6:00 minuti.) Sbaglio se affermo che investigando il rapporto tra testo e significato il tuo lavoro sottolinea la relatività del significato?

Alejandro Cesarco, still from the video The Inner Shadow, 2016

A: Con relatività intendi…

F: Intendo polisemia, intendo dire che il testo non è portatore di un significato soltanto ma di una molteplicità di significati. Mi spieghi questo che è un altro punto fondamentale della tua produzione artistica?

A: Credo che forse la distinzione tra l’atto del leggere e quello del guardare cui accennavi poc’anzi abbia a che fare con i diversi livelli di attenzione. Una delle cose che il mio lavoro esige è questo concetto della ri-lettura, il rallentare e guardare nuovamente alle cose da una differente prospettiva. E forse questa idea di un significato che è effimero o fuggevole o incomprensibile è legata alle diverse strategie narrative impiegate all’interno dell’opera. Solitamente le storie che racconto o quelle che cito hanno a che fare con un segreto di qualche genere, sicché la storia viene costruita intorno a un vuoto, intorno a qualcosa che è stato negato e da qui uno stato di incertezza che non permette la totale comprensione dell’opera. Quando dico segreto non intendo un enigma ma mi riferisco al fatto che a molti temi si fa solo allusione, che molto rimane escluso dalla narrazione.

F: In riferimento al tuo lavoro è evidente che ti stai muovendo in direzione diversa da quella dell’arte contemporanea di oggi dove tutto va verso il digitale, dove tutto è così veloce.

A: Lo dici in una accezione positiva, vero? (ride)

F: Certamente! Per me è un aspetto molto interessante! Non direi che costringi ma in qualche modo inviti lo spettatore a prendersi del tempo per contemplare le tue opere.

A: Credo che sia quello di cui abbiamo appena discusso, i diversi livelli di attenzione o i diversi modi di guardare.

F: Lo trovo molto affascinate.

A: E credo che sia una forma di reazione alla contemporaneità. Non deve necessariamente essere in questo modo.

F: Noi possiamo cambiare lo stato delle cose.

A: Si, ci sono delle alternative. Non è detto che un’altra modalità non debba esistere, tutt’altro, ma non è l’unica possibile.

F: In riferimento alla mescolanza dei tuoi linguaggi, quello descrittivo e quello visuale, come esplori la dinamica delle relazioni umane quando passi dall’uno all’altro, dalle parole alle immagini?

A: Credo che ci siano alcune cose che oltrepassano il linguaggio e alcune altre che vanno oltre l’immagine. Quando i due linguaggi si uniscono si crea in qualche modo un ambito di complementarietà, ma non so se era questo quello che mi chiedevi …

F: Si, era questo che volevo sapere perché mi è sembrato che tu usassi le immagini come le parole e le parole come le immagini, che ci fosse una compenetrazione totale in qualche modo. A volte non ho percepito la differenza tra l’uso di un medium e l’altro, come se coesistessero perfettamente nello stesso spazio. E’ solo un’impressione la mia, non so se corrisponde al vero.

A: E’ una valida lettura ma non so se operano nello stesso modo. C’è una concretezza nel linguaggio che invece nell’immagine tende a perdersi forse.

F: Parlando del tema della memoria che è un altro caposaldo del tuo lavoro, posso chiederti, in riferimento alla tua infanzia, qual è il primo ricordo che ti viene in mente?

A: (sorridendo) Questa intervista potrebbe trasformarsi in una seduta di terapia…

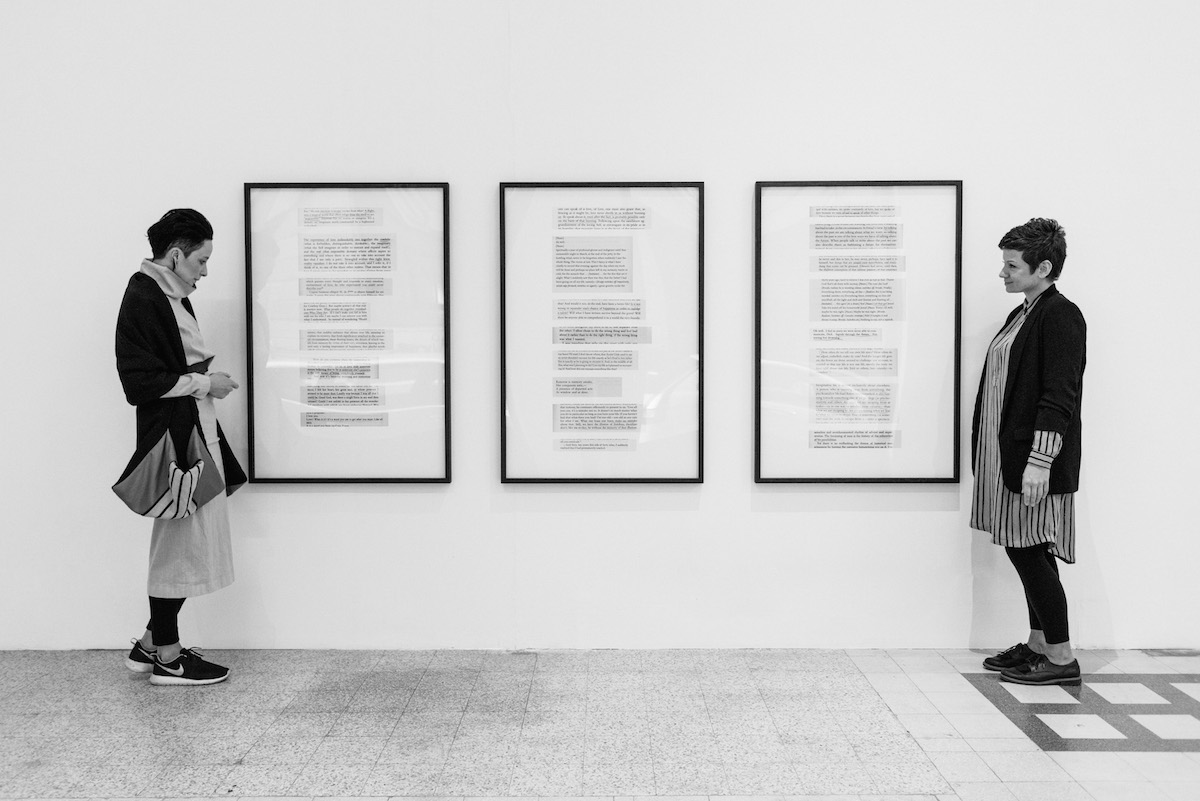

F: (sorridendo) In effetti abbiamo Freud qui con noi! (N.d.r. mi riferisco all’opera alle nostre spalle Der Familienroman (The Family Novel), 2017 una rilettura fotografica dell’edizione spagnola della raccolta Opere di Sigmund Freud, appartenuta al padre dell’artista. Cesarco legge Freud attraverso le lenti dell’autobiografia contemporaneamente alle sottolineature e annotazioni del padre. Queste divengono come la sceneggiatura – al contempo descrittiva e profetica – della storia e delle dinamiche della sua famiglia).

Alejandro Cesarco, Der Familienroman (The Family Novel), 2017

A: Il primo ricordo… non è il primissimo ma è quello che mi viene alla mente. Io, all’incirca all’età di cinque o quattro anni, che sto sulla spiaggia. Mi ricordo che c’era mio padre, riesco a sentire le mie sorelle, ma loro non sono nella scena, e siamo di fronte all’acqua.

F: E dove ti trovavi?

A: In Uruguay.

F: Quando ti sei trasferito a New York?

A: Quando avevo 22 anni.

F: C’è un altro aspetto molto interessante del tuo lavoro che è, sempre parlando di memoria, il divario esistente tra ciò che è accaduto e ciò che riusciamo a ricordare, tra il fatto in sé e la ri-narrazione dello stesso. Puoi approfondire questo punto?

A: Penso che questo alluda al concetto di malleabilità della memoria, al fatto che essa non abbia struttura rigida. Ogni nuovo racconto è in qualche modo la sua ri-formulazione e altera la memoria stessa. In un certo senso quella che noi ricordiamo è l’ultima versione. E’ quindi anche una forma di finzione. Forse questo progetto (n.d.r. si riferisce all’opera Der Familienroman (The Family Novel) 2017) affronta anche il tema di come raccontiamo la nostra storia a noi stessi, come un racconto viene costruito e per chi, e tutti questi interrogativi.

F: Posso chiederti come la memoria e l’oblio insieme scrivono il copione delle relazioni umane?

A: Domande difficili. Intendi come scelgo di dimenticare? Ma credo che questo sia il problema: possiamo scegliere di dimenticare?

F: Non lo so, buona domanda anche questa. A volte io, noi, scegliamo di dimenticare. Non credi?

A: Attraverso meccanismi di negazione e cose del genere? Si, certo. Tu come risponderesti alla tua domanda?

F: Direi che tendiamo a creare la nostra personale narrazione delle relazioni e a tributargli il nostro personale significato. Alternando memoria e oblio portiamo dentro le relazioni il nostro personale racconto e il nostro significato, scegliendo quello che vogliamo ricordare e quello che vogliamo dimenticare. Meccanismi che si muovono su un piano diverso da quello oggettivo.

A: Forse… Ma questo vale per tutto in un certo senso. Se noi non avessimo memoria come faremmo a sapere che cosa è l’amore o il dolore? Tutto si basa sulle esperienze passate e in un certo senso non possiamo fare a meno di misurarci con loro.

F: Questa è la tua seconda personale alla Galleria Raffaella Cortese, giusto? Come lo spazio ha influenzato la mostra questa volta? Come è andata?

A: Si, giusto, è la seconda personale alla Galleria Raffaella Cortese. Ho lavorato a questa mostra in parallelo con un’altra che ho inaugurato la scorsa settimana a Chicago presso la Renaissance Society dal titolo “Song”. Quella mostra in qualche modo aveva molto a che fare con la ripetizione e la durata e, in senso lato, rendeva concreta un certo tipo di crisi di mezza età. Una mostra molto spaziosa, molto spoglia direi, composta di pochissime opere la maggior parte delle quali nascoste dietro un muro. Da un certo punto di vista è come se questa mostra fosse l’inconscio di quella. Qui si fa riferimento a diverse forme di memoria, di rilevamento della memoria. Ha un che di schizofrenico forse, nel senso che esistono diversi piani di lettura, diversi modi di approcciarla: ci sono riferimenti al privato, all’amore e ai partners, e indago la possibilità di mantenere vivo il desiderio nel lungo periodo. Ma tratta anche il tema dell’origine dell’opera, quello della carriera e della fine delle opere. C’è poi un testo fondamentale sulla creatività e sulle possibilità della creatività. C’è il rapporto con mio padre, mediato da Freud, la sua metodologia di scrittura e come anche questa diventi una forma di autobiografia. E poi, come se fosse l’interruzione di un capitolo, c’è l’altra metà della mostra: un lavoro aggiuntivo che può essere paragonato a delle note a piè pagina o qualcosa di simile. Esiste questa ripetizione formale: qui (n.d.r. nello spazio di Via Stradella 7) mio padre che sottolinea i suoi libri e lì (n.d.r. nello spazio di Via Stradella 1) io che sottolineo i miei ed è come se il tratto di questa linea disegnata fungesse da connessione tra le due opere. E ancora, il ritratto delle mani della mia partner che sembrano quasi contenere tutta la mostra.

Alejandro Cesarco, An Abridged Histoy of Regret, 2012

F: Studies for a Series on Love (Wendy’s Hands), 2015 è un’opera che sembra voler proteggere e abbracciare lo spettatore.

A: Si, una sorta di abbraccio. Ma pone anche molto l’attenzione sulla questione del supportare, le mani che permettono a tutto il resto di accadere. Quindi credo che le diverse opere aprano la strada a diverse possibili letture e interpretazioni. Quello che per me è interessante quando dò vita a una mostra è il fatto che tutti questi elementi si influenzino a vicenda e facciano nascere qualcosa di nuovo.

F: Grazie Alejandro per il tuo tempo e la tua disponibilità.

Alejandro Cesarco, Studies for a Series on Love (Wendy’s Hands), 2015

The Measures of Memory di Alejandro Cesarco – in mostra alla Galleria Raffaella Cortese fino al 28 febbraio 2018 | martedì – sabato 10 – 13 / 15 – 19.30 e su appuntamento

Foto di Elisabetta Brian

Desidero ringraziare per la preziosa collaborazione Daniela Legotta e tutto lo staff della Galleria Raffaella Cortese

ALEJANDRO CESARCO, THE MEASURES OF MEMORY (ENGLISH TEXT)

The Measures of Memory, Alejandro Cesarco’s second solo show at Galleria Raffaella Cortese flirts with the possibilities of memory as both the object and instrument of our desires. The exhibition puts in relation different methodologies of documenting, describing and accounting for the passage of time ad the forms used to recall it. As is characteristic of Cesarco’s practice, the exhibition carries a rather romantic and melancholic tone and furthers his exploration of notions of personal narrative, style, aging, influence and inheritance.

Francesca Interlenghi: Alejandro, you are frequently cited as continuing the tradition of conceptual art and narration of the 60s and 70s. I must admit I am not keen on definitions, but do you feel comfortable with it?

Alejandro Cesarco: I understand why it is used. I think it is shorthand for a lot of things, but I don’t know that it makes a lot of sense. I don’t quite know what people mean by that, or what qualities of the work they identify to fit within that tradition, because to some extent, all work is conceptual.

F: I do agree with that.

A: I think it needs further clarification. On the other hand, it is true that I am fascinated by conceptualism as an ‘ism’, as a movement, so a lot of the formal aspects of my work reference past works from the 60s and the 70s.

F: Studying your work, I would say that it often appears to be an intersection of rationalism and poetry, a mutual dialogue I might say. All your artistic production unravels in the space between your rational vision and your emotional perception. Could you tell me how your artistic process comes into being? Just to clarify, I am very interested in understanding how you find the balance, a point of contact, between the rational vision and the emotional perception in such an inalienable way.

A: I think a lot of the work concerns this tension that you expressed, in the sense that it’s almost about keeping intimacy at a distance, measuring what place it is comfortable to speak from. But it’s also about infusing these seemingly cold containers we were talking about, these conceptual forms, with what seems to be intimate content. But then intimacy is also questioned in the work, because it seems to propose something that’s very intimate, but there’s no actual anecdote being revealed. So it’s really about affect, and how meaning is felt, to some extent. But then again, just like with the word conceptual, can there be rationality without emotion? They are non-exclusive, they exist together inevitably.

F: In my opinion, everything that deals with the human being is romantic, or sentimental, maybe it is more accurate to say emotional. It is very interesting to see how language pervades your practice, and where the distinction between reading and looking breaks down in your artwork. I am just thinking about your video “The Inner Shadow” which is really amazing and very touching (editor’s note: The Inner Shadow, 2016, 8mm film transferred to digital, color, sound, 6:00 minutes). By investigating the relationship between text and meaning, am I correct in saying that your work highlights the relativity of meaning?

A: By relativity you mean…

F: I mean that the text is polysemous, that there is not just one meaning but several meanings. Can you clarify this point, please? Because it is another topic in art production.

A: I think perhaps the distinction between reading and looking you were speaking of before, has to do with different economies of attention. One of the things that the work demands is the idea of re-reading, of slowing down and looking at things again from a different perspective. And maybe this idea of meaning being fleeting, or fugitive or incomprehensible, has to do with the different narrative strategies that are employed within the work. Usually the stories that I tell or that I reference have to do with a secret of some kind. So, the story is constructed around a vacuum, around something that’s being withheld, and there is a level of uncertainty that does not allow the work to be comprehended. When I say secret I don’t mean enigma, I mean that there is so much that is alluded to, so much left out of the narrative.

F: Thinking about your work, you are going in such a different direction. Contemporary art seems to go towards the digital, everything is so fast.

A: You mean that in a good way, don’t you? (laughs)

F: Of course! It’s very interesting to me! I would not say you force, but you invite the visitor to take some time to contemplate your artwork.

A: I think this is what we were talking about just now, about the different economies of attention, or habits of looking.

F: That’s so fascinating to me.

A: And I think it is kind of a reaction to contemporaneity. It doesn’t need to be this way.

F: So, we can change it.

A: Yes, there are alternatives. It’s not that the other option doesn’t need to exist, it can, but it’s not the only mode.

F: Talking about the combination of your descriptive language and your visual language, how do you explore the dynamics of interpersonal relationships while shifting from one language to another, from words to images?

A: I think there are certain things that exceed language and certain things that exceed the image. In some way, there is a complementary position that happens when the two are joined, but maybe that’s not what you’re asking…

F: Yes. I wanted to know, because I thought that you use images as words, and words as images, and they interpenetrate in a way. Sometimes I don’t feel any difference between one medium and the other, they coexist perfectly in the same space and the same habit. That is just an impression. I don’t pretend to believe that I hold the truth in my hand.

A: That’s a valid reading, but I don’t know that they operate in the same way. There’s a concreteness in language, whereas the image tends to be looser, maybe.

F: Talking about memory, which is another topic that is firmly established in your work. May I ask you, talking about your childhood, what is the first memory that comes into your mind?

A: (smiling) This could turn into therapy…

F: (smiling) We have Freud here! (Editor’s note: referring to Der Familienroman (The Family Novel), 2017 a photographic re-reading of the artist’s father’s Spanish edition of The Complete Works of Sigmund Freud where Cesarco simultaneously reads Freud through the lens of auto-biography and looks at his father’s underlining and notations of Freud’s text as a script of his own family story and dynamics.)

A: The first memory is… it’s not my earliest memory, but it’s just a memory that came to mind. It’s me at about age five, four, laying at the beach. I remember my father being there, and I can kind of hear my sisters, but they’re not in the scene, and we’re facing the water.

F: And, where were you?

A: In Uruguay.

F: When did you move to New York?

A: When I was 22.

F: There is another interesting point in your work which is, talking about memory, the gap between what happened and what we can remember, between the event and the re-telling of it. So, can you tell me something about that?

A: I think it just hints at the malleability of memory, how it’s not something fixed. Every re-telling in a way re-formulates it, and changes the memory itself. So, in some ways, what we remember is the last re-telling. It’s hence also a form of fiction. Maybe this project (points to Der Familienroman (The Family Novel) works) is also about how we tell our story to ourselves. It conveys this idea of how a narrative is constructed, for whom, and all of these questions.

F: May I ask you how both memory and oblivion write the script of human relationships?

A: These are hard questions. You mean how I choose to forget? But I think that’s the problem: can you choose to forget?

F: I don’t know. That is a good question too. Sometimes I, we choose to forget. Don’t you think so?

A: Through repression, and things like that? Yes, of course. How would you answer your own question?

F: I would say that we tend to create our own narrative and our own significance about relationships. We make our own narrative and we carry our own significance into the human relationship by using memory and by using oblivion. By choosing what we want to remember and by choosing what we want to forget. It’s not something that we deal with objectively.

A: Perhaps… But that’s true of everything in some ways. If we didn’t have memory, how would you know what love is, or what pain is? Everything is based on past experiences, and in a way, we can’t help but measure up against them.

F: This is the second time that you are showing at Galleria Raffaella Cortese, right? How did the space influence your exhibition this time? Can you tell me how this exhibition came to go?

A: That’s correct, it’s the second show at Galleria Raffaella Cortese. I worked on this show in parallel to a show that I opened last week in at the Renaissance Society in Chicago, called “Song”. That show in some ways had a lot to do with repetition and duration, and very broadly speaking, physicalized a mid-life crisis of sort. It is a very spacious, very sparse show. There are very few works in that show, and most of them are hidden behind a wall. So, in some ways this is like the unconscious of that show. Here different forms of memory are alluded to, different forms of tracking memory. It’s slightly schizophrenic maybe? In the sense that there are very different modalities, different forms of address happening in the show, there are references to the domestic, to love and partners, and the idea of sustaining desire in the long term. There’s the idea of the provenance of works, and of a career, and where the works end up. There’s a foundational text on creativity and the possibilities of creativity. There’s my relationship with my father, mediated through Freud, and his own writing methodologies, and how that also becomes a form of autobiography. And then there’s like a chapter break, and the other half of the show, the additional work, that almost function like footnotes to the show, or something like that. There is this formal repetition: here (editor’s note: at Via Stradella 7) there is my dad underlining his books, and there (editor’s note: at Via Stradella 1) there is me underlining my books, so this line drawing kind of connects the two. And then there’s the actual framing of my partner’s hands that in a way contain the show.

F: Studies for a series on Love (Wendy’s Hands) 2015, seems to be protecting and holding the visitor.

A: Yes, it is like an embrace. But it’s also very much about support, the hands that enable everything else to happen. I think that in some ways, there are very many narrative avenues opened by the different works. What’s interesting about exhibition-making is that it allows for these elements to rub off against each other, and create something new.

F: Thank you Alejandro for your time and your kindness.

The Measures of Memory by Alejandro Cesarco – on view at Galleria Raffaella Cortese until February 28th 2018 | tuesday – saturday 10am – 1pm / 3pm – 7:30pm and by appointment

Photos by Elisabetta Brian